Report of Ben Kinmont's presentation at Bâtard Festival

00:00 Introduction by Florence Cheval

06:10 Ben Kinmont: I consider myself a ‘project artist’. This is a term from the US, early 1990s. It is a term used for practices that aren't necessarily about making single objects.

BK Reads first slide "Towards a definition of project art":

An effort that runs through a lot of my practice is to try to develop a language to talk about my practice. This type of practice does not give much prominence to the art institutional space.

09:11

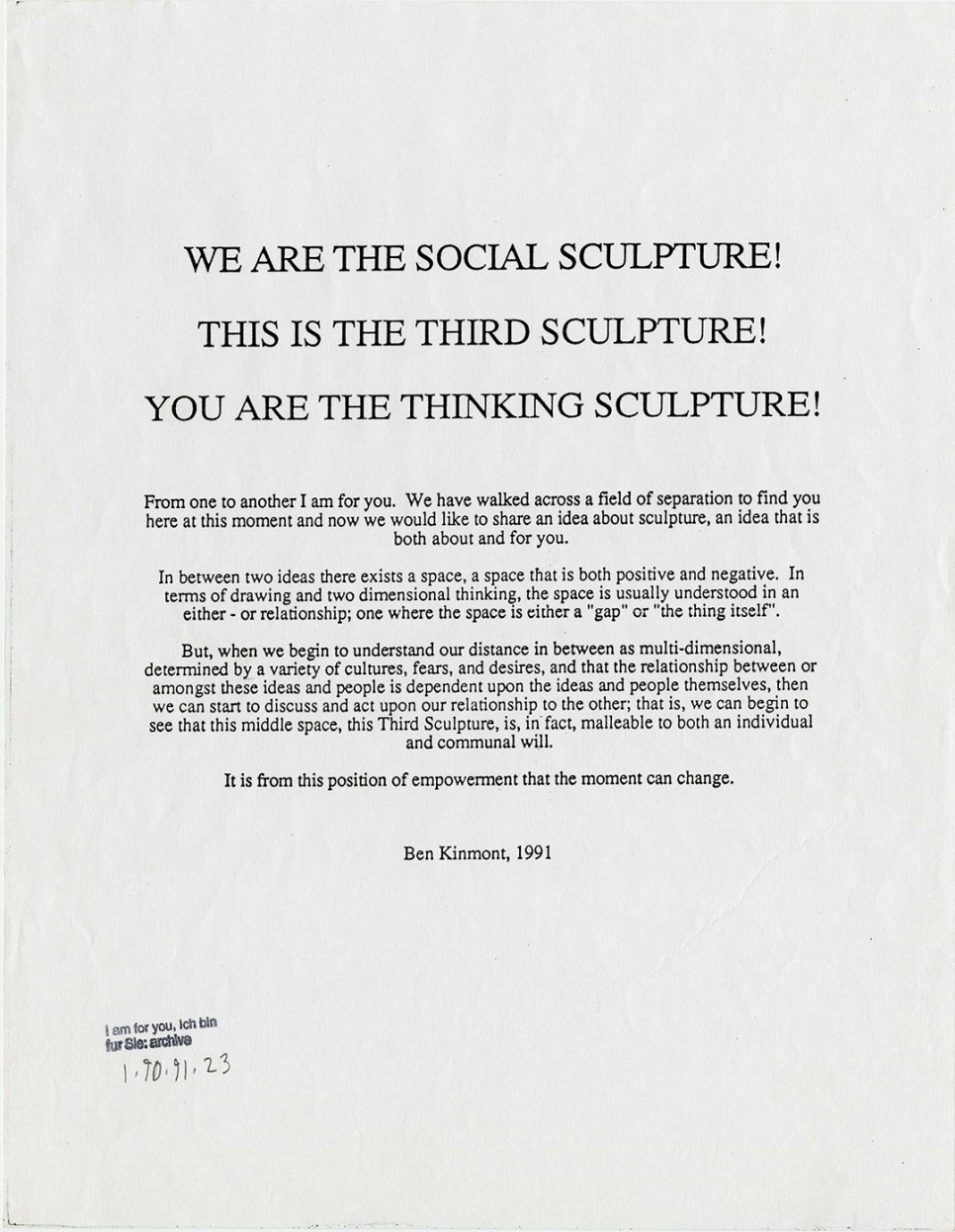

First large public project I did on the street (refers to hand out text). I was interested in Joseph Beuys' idea of social sculpture.

I studied American philosopher William James, specifically the idea of truth-making processes. Much of what happened in universities at the time were reactions to the post-structuralist ideas of non-communicability and the impossibly of language. I was a bit reactionary to that. I needed a syntax to speak about my projects, which were on the street weren't about single objects and occurred over a long period of time. Within I am for you, (early 1990s in NYC and Cologne), we spoke to 11.750 people over a 4 year period. I wanted to present three ideas. I did a reiteration/summary of Joseph Beuys’ social sculpture, I spoke about the idea of the cognitive process as a sculptural process (the way in which we receive stimuli and come up with ideas, we could understand that as a form of sculpture, of art making), which I call ‘The Thinking Sculpture’. Social sculpture: We, relationship individual-society. Thinking sculpture: I. Missing is the space in between. This is what I conceive of as "Third sculpture". It could be the space between you and me right now; it could be the space between dominant culture and a subculture; it could be the space between two different ideas; a physical space between two objects. As soon a space is identified, it becomes a point, that creates new spaces in between. Space for Third Sculptures. Third sculpture is like a verb, projects in motion. My distinction between the Social sculpture, the Thinking sculpture and the Third sculpture is a result of me trying to come up with a syntax to discuss these kind of projects where the objects involved (flyers for instance) or the moments of ‘performance’ on the street were not the piece itself. A sum of all these things.

14:40 Footage I am for you. Here, discussing about society is considered as a sculptural activity.

17:00 The dialogue about art practices that addressed a larger community at that time used to be rather exclusive, not involving the people they were about. We needed to open up, let ourselves be criticized, be told it was bullshit, or try to justify it to the people about whom we were making these work. After the I am for you project I wished I had documented more the response I had from people. Subsequent projects were rather questions-based.

20:53 Question by Ronny Heiremans: How did people respond to you? BK: This depended on the neighbourhood, there were all kinds of people who reacted. I try to not lower the discourse to keep them popular, I keep them as true to how I would like to discuss with a fellow artist. But the offer was made to everybody. People asked what I wanted to sell, if I were from a political party, or from a religious group. Profits were equally distributed over the people who participated. Co-authorship through participation makes it easy to speak about the meaning of a work.

23:30 BK started a publishing project, Antinomian Press. BK: The Antinomians were radical protestants in16th century England that were accused of being anarchists. Common ownership of property came into the English language first during this time. They were avid pamphletteersrs. This was a precedent that I liked a lot. People who didn’t own any land and were itinerant labourers were called "Masterless men". The English crown was in need of money because of the war with Spain. They were privatizing the commons. After the civil war, the brief republic in England with Oliver Cromwell needs these masterless men to fill the army. He allowed these radical groups to continue to exist.

27:16 I was doing a project at Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford CT. I went into the archive of Chris D'Arcangelo, the assistant of Daniel Buren in the 1970s. He was interested in issues around labour. He was proto-institional critique, and arrested a couple of times for interventions in museums. I made an Antinomian Press publication about this which I distributed in the Louvre, together with art students.

32:06 Another project was about authorship and maintenance: It's easier speaking about art while doing the dishes (1995)." BK shows images of people filming him talking about his art while doing the dishes in a museum restaurant. The people watching and filming can sign his arm as co-authors.

35:40 Materialization of life into alternative economies. Exhibition BK made after leaving his galleries. One of the reasons to establish Antinomian press was to be clear with my own discourse. Another element of that was to start curating exhibitions. Referring to Lucy Lippard's book The dematerialization of the art object, some of the artists participating in the book actually wanted to speak about the materialization of life.

39:19 Exhibition: Promised Relations (from 1996). When I do a project, I create an archive. An archive can be exhibited and there are contracts for that. Promised Relations is about those and other contracts. One of them is Seth Siegelaub’s and Bob Projansky's The Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement.

41:33 BK speaks about the business of bookselling, which originally was a way of making some money for his family: Sometimes a nicer sculpture is to be able to provide a living for your family (1998) is a project that reflects on it. Antinomian Press should be considered not as a symbolic project but as an actual economy. I specialize in rare books. The people I do business with typically don't know it's an art project. It exists in both histories and discourses simultaneously.

48:52 BK did a project for Documenta 11 (2002, Okwui Enwezor): Movable Type, No Documenta. One reference is Seth Siegelaub’s insight that early conceptual artists didn’t need exhibition spaces anymore, but could realize their work through publications. Another reference is Ian Wilson’s idea of conversation as sculpture. Before Documenta opened, I spoke with people on the street about the most meaningful things in their lifes, and if they could think of those things as art. We made summaries of their responses in German in English, co-edited it with the interlocutor and distributed a printed version of it in the neighborhood, all within one day. For me, this was about locality and value, meaningfulness and the domestic sphere. During Documenta itself, the same material was printed on the same devices. Institution of Documenta became a distribution centre of a group show for free.

54:51 BK speaks about his project Shhh (2003), again on the phenomenon of 'conversation'. People asked to have a conversation amongst their family, without him present. This time, these conversations were kept private. The only thing BK asked from them, was their family name, the date of the conversation, the colour ink they wanted them to use, and the size of the engraving that this would turn into. BK made the engravings in an edition of three: one free for the family, one for the archive of the project, and one for the institution.

58:08 During the Whitney Biennial, BK invented a way to have the Whitney pay for the distribution of the pieces returning to the participating families. BK: You’re constantly trying to get people to participate in your projects, but you’re never the one to participate. I wanted to know what it is like and I asked my family to participate. We all had a conversation and it’s a special piece for me, I have it hanging at my house. I do look at it and I remember what we talked about.

1:01:30

BK’s most recent work is about upcoming mid-term elections in times of Donald Trump. He placed advertisements in New York Times and Washington Post.

1:11:00 BK speaks about reasons for leaving his art galleries. Reconsideration of what he thinks of as success. Finding discursive space and accessibility are part of that. There are usually only low budgets for projects happening on the street. Being closer to the boundary between art and everyday life is an important factor. Removing oneself from the economy of art galleries is very satisfying. It offers opportunities for sustainable practice and a horizon of decisions that one makes. What is the value structure in which you understand your work? How is it circulating?

1:15:54 A BK project in Centre Pompidou On becoming something else (2009). Seven biographical paragraphs on artists who left the art world. It points out that leaving doesn't need to be understood as a failure. That their practice had to be called something else tells us something about the art world.

1:18:55 Question by Katleen Vermeir: Within your project on the street, I am for you, you paid people as co-authors of the work. Do you always work like that? BK: That’s the only one that went specifically like that. In the beginning I was much more 'contractual', trying to be honest and upfront. But I found out that that actually doesn't encourage. Momentary meaningfulness of informal but interesting encounter was more relevant to me and more suitable to the projects.

1:21:30 Question by Katleen Vermeir: How about the recording devices? How does their presence influence the projects? BK: That slowly disappeared because it was awkward and less functional. I use textual information to communicate about my projects. Something similar that happened: I would write a project description for my projects when they were exhibited. That description became an icon for each project, more important than its images. This role of the project description and its potential fictionality was of interest to me. I did a project with grad students in San Francisco. Within the rare book world, there exists a genre of bibliography that is called Bibliotheca Chimaerica: library catalogues that list books that don’t exist, imaginary books. The first person who ever did it was Rabelais. A lot of literary figures (Borges for instance) have done this, often as a political critique when actually publishing a book wouldn’t be possible. With the grad students, we did an Exhibitio Chimaerica: write a project description of a project that is important in art history but that never occurred. By a real historical figure or an imaginary one. We published them as though they had happened. I wrote an introduction, and if you didn’t know they didn’t happen, you could believe that they had actually happened. I wanted them to get a sense of the degree to which project description writing is fictional. It’s the case with any news that has been written: it’s not the event, it’s the story of the event. That’s when Lucy Lippard did write to me: ‘Oh, I didn’t know Robert Smithson did this piece, this is amazing.’

1:25:33 I’ve done that also with curators. I gave an assignment to curatorial students in the Museum Studies programme in Rennes to create an imaginary exhibition by an imaginary curator. We were talking about ‘urgency’ at the time, which is a big issue for me and my work: “What’s urgent in your life? What’s urgent politically? What leads what you do?” …and using this as part of the content of your work. The students made up a curator and wrote a description of a fictional exhibition. An exhibition format that was not typical for the time period that they chose and dealt with issues of urgency. A history of alternative exhibition practices that never happened. They set a number of them in the future. So much is based on facts, “I handed out 11.750 flyers over this many hours and I spoke to this many people and this is what it’s sold for”, but there is also a fictional quality about this. Not being conscious of the storytelling aspect of it. This is also about value and discourse, how you tell the story and how you create the value of the piece.

1:27:36 Question by Caroline Dumalin: Did you show your family the advertisements of your most recent project? BK: Yes, I did. It was meant to be harsh and catch the eye as one browses the newspaper. I wanted to address the reader specifically. Even folks on the left don't acknowledge our culpability for what has happened, while we are responsible and we need to take action. The personal is political. I'm not interested in doing things for symbolic reasons, it’s more interesting for me to find out how to write an ad for the NY Times than to do another exhibition.

1:30:54 BK about changing the economic environments of one’s practice. When you start to take control of your budget and economy, one begins to realize how much money it costs to be involved with galleries and museums. Once one becomes aware of that, one can start playing with that. Once one settles in to becoming independent from the capitalist gallery system there are a lot of opportunities and situations that emerge. Then, the question arises: Who do you want to know about it? The artists who depart from the art world are artists who decided that they didn’t need the art world to know what they did anymore. They needed politicians, social workers or farmers to know what they did.

1:36:20 Question by Katleen Vermeir: Why do you work with a gallery now? BK: I work with Air de Paris, a gallery in Paris. They are people that are very important to me. They asked me to join the gallery. They help out a lot, practically, and make sure people know about the projects. For me, it’s more discursive than economic. It offers another way of reflection, things that I can't say otherwise. I don’t think galleries shouldn’t exist, I just don’t think they need to always be that important.

1:38:49 BK: Why do I even bother with the term sculpture? It is a way of making what I do more accessible to people who may have never been to a museum. Thinking with other people about art in an expanded way.

1:40:20 About ethics. With anthropology grad students, we wrote a text about ethical considerations in project art. When you displace and art discourse into a non-art space, what’s the ethical situation of your own actions in that space? What are your relations with people contributing? It turned out that it was almost identical to field guidelines that exist in anthropology of how to represent a subject, how to interact with with a community. Anthropology has been dealing with these issues for a very long time. The representation of the other and the imposition of yourself into the other community. One starts to find connections to other value structures in other discourses.

1:42:30 Question by Jesse van Winden: What are things that working with a gallery allows you to speak about, and how? European art institutions aren't so hung up with commercial considerations. After I left my galleries, I was out of mind and out of sight. I think I was the only artist in the Whitney Biennial without New York representation. In America, the commercial nature of your relationship to your gallery is pretty severe. Whereas with Florence from Air de Paris, if I have a project and I need a team of people to help me realize something on the street of Paris, she’ll say: sure. I'm also very interested in community health organizations. I did a project with Air de Paris where I made paintings which said “There is also a need outside of here” at the bottom of the canvas. I asked the gallery to give 100% of the proceeds if the work was sold to the nearest-by community health organization. I wanted collectors to consider that their action would help an organization that they probably never knew existed down the street. To redefine the geography of the gallery in a vernacular way. Florence would say: of course. Not a lot of gallery dealers would do that. Sometimes it’s interesting to have a gallery in order to reflect on those kind of things.

1:46:50 Question by Michiel Reynaert: How do you relate to practices such as Artist Placement Group? BK isn't familiar with APG. He elaborates on the tradition of service providing, and his projects where he takes up certain professional roles, such as that of the dishwasher. It was about maintenance for sure, but even the food projects I do are really not about food, but about something else that’s created in that situation. It’s asking questions about issues of trust.